Note: This entry has been restored from old archives.

We stuck close to Cambridge on Saturday and Sunday, wandering the town and driving the fens. On the latter, the history of the landscape is intriguing. Once the whole area was boggy wetland and many of the historic sites and towns were considered islands, as only the higher and drier areas were originally settled. Through the centuries the landscape has been transformed into fertile pastures that are usually not under water, aside from the occasional flood. Ditches and dykes criss-cross the landscape. I hope to learn more about it all some day, for now here’s what we did…

Saturday: St. John’s College, Hemp, Books, and Ale

We decided that we must visit at least one of the colleges while we’re here. In the end one is as far as we got, and that one was St. John’s since it was the first we found that was accepting visitors. As a tourist you pay £2.80 to enter, this gives you a guidance pamphlet with interesting notes and, I guess, peace of mind (you could probably just wander through as there is a regular traffic of locals and students – also, you could just wander in from the backs.) Thanks mainly to the more interesting points highlighted by the pamphlet the wander through the college was a worthwhile experience. Most of the more obvious questions that came to mind were answered by the terse document, and many less obvious points of interest were highlighted. Especially amusing are details in the chapel’s large western stained glass window.

Our examination of the college took us well into the afternoon, taking more than two hours in total. We’d started out late that day, sleet and heavy wind keeping us inside-looking-out. After St. John’s we headed towards the car and bought ourselves hempen scarves from a hemp stall at the market, Kat also picked up an oversized “baker boy” hat she liked from another seller. Our next adventure was to take us out of town and involved ale, so we dropped the car back at the hotel and caught a bus back in. We’d settled on driving that morning and paying an exorbitant parking fee, just to avoid some of the weather. In the end the parking, for three hours I think, was £8 – the taxi would have been the same each way so driving was cheaper. I’m glad we didn’t try driving into town in the afternoon though, it was near to 15:00 when we drove out and we noticed all the parking spots were full and there were traffic queues leading for a couple of miles out of the town centre! The way out was clear thankfully.

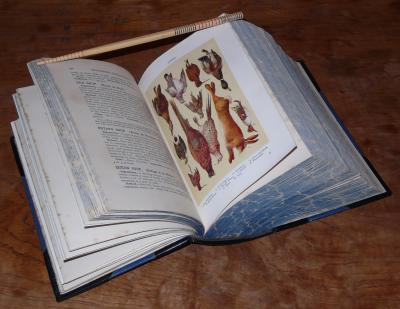

To get to the best bus stop near the hotel requires a five minute stroll along a narrow path that connects the business park the hotel is in to a south-eastern suburb of Cambridge. The path is narrow, enclosed on each side by a high wire fence and shrubby bushes, and after a rail crossing passes between an army exercise yard on one side and a body of water on the other (this latter a private fishing reserve.) The suburb our bus stop is in isn’t on a route out of Cambridge so the bus got into town without any delay. We found ourselves with a little over an hour to kill before moving on to our planned train departure. In this time we found a wonderful bookshop, which I’ve written about separately (will post later this week), we also had tea and scones at “Aunties” near the market square – the latter was good but unexciting.

We caught the 17:35 service from Cambridge to Kings-Lyn and hopped off five minutes later at Waterbeach. A few minutes walking and we were at The Bridge, and found ourselves before 20 cask ales! I’ve written more about this separately (will post later.)

The ales pretty much wrapped up our day, we left The Bridge at 21:30 and thanks to incorrect advice from the barman waited at the station for 35 minutes until the 22:15 train took us back to Cambridge. (We don’t blame the barman at all, it’s our own damn fault for not making a note of the timetable!) While waiting in the cold we noticed something interesting, we heard a strange popping whumphing noise, almost like distant fireworks. It turned out that at one end of the platform was a track switch, alongside the rails near this was an enclosure full of gas cylinders, there was gas being let into an enclosure alongside the switching mechanics and this was being ignited at short intervals. Keeping it warm, and functioning, in the cold weather. In time, and on time, our ride back to Cambridge arrived. We reached the city far too late to catch a bus so, me being me, we discovered that the walk between the Cambridge Rail Station and the Holiday Inn Express only takes around 35 minutes (at a fast pace for an unladen 4’8″ person.)

Sunday: Houghton Mill, and Ale

Looking out the window this morning we saw whiteness, overnight snow had coated the landscape. We were somewhat slow in getting out and about again, not quite sure what to do. Our vague plan was to head down to the Lordship Gardens, but given the general slushiness this seemed less appealing than before. So, as a replacement, we selected Houghton Mill as it seemed a more enclosed destination.

The drive up to Houghton from Cambridge took around 30 minutes, mostly a fast zoom along the A14. Driving into the town the first thing of note is the thatched roofs, there’s even a clock tower in the town square that has a thatched-roof shelter as a base. The mill is found down a short and narrow road running from the south of the square, a wall on the right side and a bust of the most renowned head (and philanthropist) of the milling family on the left. At the end of the road you turn through a gateway on the left and see a field (and caravans) ahead, a small tearoom to the right, and further right, unmistakably, the mill and river. The field is usually green I imagine, but this day it was mainly white with a thin crust of snow. There were also two crude snowmen to be seen, looking bent and dirty – snowtramps maybe.

The mill doesn’t open its doors until 13:00 and we were early so took a quick and very cold stroll along the path that begins with the passage through the mill. They have an interesting lock around the bend, very different and much more industrial looking than those we’re used to seeing on the Grand Union canal. That’s as far as we went, as we were not properly prepared for the cold or the mud. In sunnier, and drier, times we’re keen to revisit as there are extensive walkways along the river Orse. We returned to the mill and had tea and scones in the tearoom, much better that what we’d had in Cambridge the previous day!

Just after 13:00 we entered the mill, paying a small fee to the National Trust for the privilege (and making sure we signed the forms that ensue the government adds another 25%, UK tax-payers rejoice.) The mill was excellent, well documented, and in good order. Two things of note are that the mill, in part, is functional, and that there is a hydro-generator fitted in the sluice. The latter typically generated enough power for 10 homes, which is neat. The mill was brought to working order just before the turn of the millennium, thanks to a lot of work contributed by the army (maybe airforce.) They have a photo-album on the ground floor that is worth a perusal.

Normally they have the mill working but they couldn’t on this day since the Environment Agency computer had decided that the sluices needed to be open, preventing flooding I assume, so there wouldn’t have been enough power to run the mill. This was a pity for us since it meant we couldn’t buy any flour! Maybe next time.

All in all our visit to Houghton Mill was very enjoyable. It seems to be well suited to youngsters, fitted out with many action-models of mill mechanisms, some very elaborate (turn on the tap, turn th handle, etc.) We’re considering heading back that way in summer, with a tent as there is a camping ground nearby. I’d be great if there’s somewhere you can have a small fire, imagine it: damper made with flour milled only a few hundred meters away!

We departed the mill after a couple of hours and wound our way back towards Cambridge on back-roads. Taking in views over the flat expanses of fenland, seeking out mounds marked on the OS maps (unsuccessful), and eventually finding ourselves in Histon.

Histon was added to the route because it is the home of a certain The Red Lion that comes well recommended complete with a history of CAMRA branch and national “pub of the year” wins. The reputation is deserved as far as we’re concerned! The full details are a story for another article, to come.

After a couple of halves we headed back to the hotel with take-away beer (await other article for details), popping into a place called Yu’s Chinese for dinner. This place does pretty good food, generous serves, and at a decent price. It’s on Newmarket Road just past the Perne Road roundabout on the way into Cambridge.

Bloated with Chinese we eventually arrived back at the hotel to drink our four pints of real ale, relax, and, for me, write the words before you.

Monday: Anglesey Abbey & Lode Mill

Time is short and thus my description of this day will follow suit. We drove out to Anglesey Abbey, a National Trust property about 15 minutes from Cambridge, and wandered the grounds and house (abbey nee priory.) It’s excellent and entirely worth the £9.50 entry fee. When I first came to the UK I joined the National Trust since the £20 membership fee was accounted for after only two property visits and a few uses of National Trust car-parks. However, once you’re over 25 (my word, is is really that long since I first hit this little island?) the fee more than doubles and being vehicularly-challenged it didn’t seem worth the price. Anglesey Abbey changed my (our) mind, since we expect we’ll visit at least once more this year. So two times 20 quid is 40 quid, and membership for a couple is 77 quid … £37 should be a pretty good incentive to see some more great National Trust properties. Honestly, I’ve seen quite a few in the last three years and they’ve all been excellent.

In short: the gardens alone are worth the trip, and the house is an interesting addition but less interesting than the mill. The Lode Water Mill was the second mill we saw over the weekend and like Houghton Mill it has also been restored to working order. At this mill we could actually buy flour though! We also bought some oat meal for the making of our morning porridge. The wheat (“corn” in the old speech) milled comes from a National Trust property, the nearby Wimpole Home Farm (which also supplies the wheat milled at Houghton Mill.)

The history of the property as you see it today is mostly not so ancient, and the late First Lord Fairhaven seems like a dude I’d like to meet. I’m not sure if he’d be so keen on my ignoble presence however, though he was “new nobility” so possibly less picky about such details. The most ancient part of the property is the dining hall, the structure of which actually dates back to the original monastic building that occupied the “island.”

There’s far more observations I’d like to make about this property than I have the time for. I expect to visit Anglesey Abbey in the summer, maybe I can go into further detail then.

We whiled away most of the day at the property, visited an unexciting pub, picked up some cheese and snacks on the way back, and ate in our hotel room. Here ends the day.